Why was GLP-1 not a biotech success story?

On the realities of contrarianism in biopharma

It’s been remarkable to watch the unfolding of the GLP-1 revolution. The drugs are set to generate $100bn in annual sales by 2028 and have already brought about immense societal impact. Yet I have to wonder, why was it not a biotech company that led this revolution when they already contribute two-thirds of newly approved drugs?

The most obvious explanation might be high trial costs or pharma’s track record in diabetes and metabolic disorders, but there is a deeper factor at play. In my view, obesity drug development for biotechs was discouraged until very recently, largely due to the challenge of gauging the true value of a drug in an emerging market. I explore how contrarian thinking is seldom rewarded in biopharma and how this dynamic is amplified by the pharma’s powerful hold on the industry’s incentives.

Incentives that were at play for obesity drug development

Suppose, in 2010, you believed that an effective, tolerable weight-loss drug would be worth $100bn. What might’ve stopped you from developing Mounjaro?

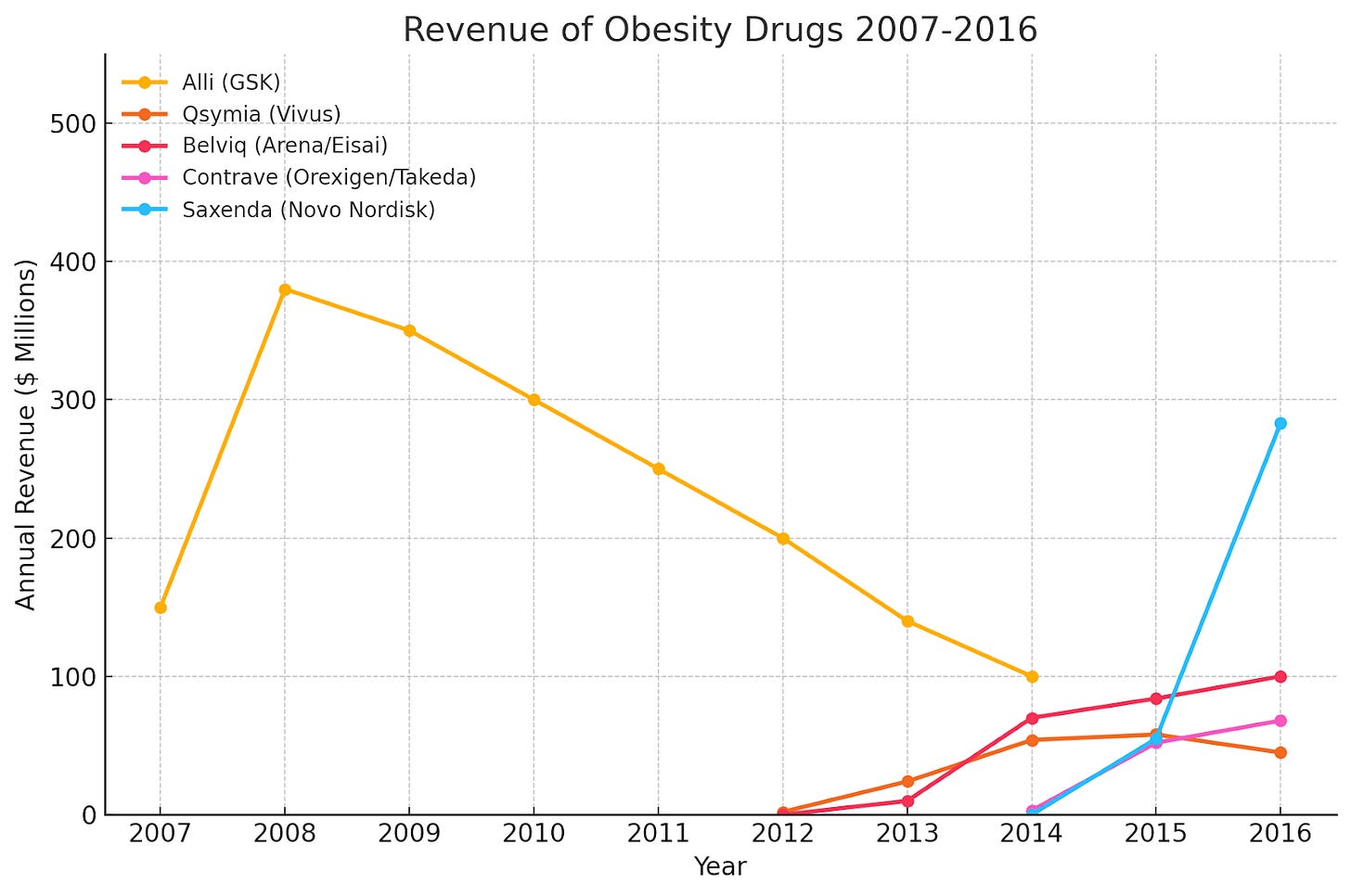

The main challenge you’d run into is that investors wouldn’t give you money. Let’s look at what was going on in obesity at the time to better understand this, starting with the revenue of obesity drugs during 2007-2016.

You’ll notice that the two drugs that launched in 2012 barely scraped $100mm after 4 years of launch, and even GSK’s OTC offering didn’t surpass $400mm/yr. As intuitive as the value of a weight-loss drug was, these sales numbers didn’t seem to indicate that they were anything close to a blockbuster. Of course, weak efficacy and poor safety profile played a key role here. Take a look at the efficacy / safety drugs below:

A 10% reduction in body weight was often cited as the threshold for widespread adoption, but these drugs seemed to still be far from it. Safety concerns also emerged, with drugs like Acomplia and Belviq ultimately withdrawn from the market for psychiatric risk and cancer risk respectively.

Another meaningful challenge was on the commercialization side. Physicians & patients were simply not that educated on these offerings, and the payors were unwilling to meaningfully reimburse the drug. A quote from a 2015 RBC Capital Markets report by Simos Simeonidis illustrates this:

The obesity market was clearly not ready for the arrival of Qsymia and BELVIQ. There were low levels of physician and patient awareness of the new pharmacotherapies, physician unwillingness, lack of experience and exposure with treating obesity with pharmacotherapy in general, and lack of reimbursement.

Given these dynamics, obesity drugs were simply not an exciting space for investments. On the scientific risk side, it appeared unlikely that the next obesity drug would succeed against all odds when numerous candidates have historically shown limited efficacy & tolerability in the clinic. This dynamic is what leads to the “graveyard effect,” where areas with a series of failures are ignored, even when it may be the area for the most outsized returns. Some areas today that you’d find this sentiment are glioblastoma, AAV gene therapy, or a number of neurodegenerative disorders. And on the market side, there wasn’t a clear signal of robust market demand.. Sometimes you find the pull to be so powerful where drugs with limited profile can still succeed commercially. A primary example today is Exondys and Vyondys for Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy which sell $1bn/yr collectively despite limited efficacy.

Another dynamic that exacerbated this was that investors rely heavily on pharma for exits, and there was little pharma M&A interest in obesity. Given that pharma M&A is the most preferred exit path for investors, areas that lack a clear M&A interest become much more difficult to invest in.

Let’s take a step back - why has pharma M&A become such a cornerstone in the biotech ecosystem and investing? To highlight a few:

It provides a nice multiple to the current share price

Gives liquidity to investors, since large positions are hard to exit

The alternative of launching a drug independently is notoriously difficult and risky

So in some ways, biotechs are not just valued by the NPV of the drugs but rather how much a pharma might acquire them for. This is why investors keep their eyes peeled for what pharmas are interested in, so they can go invest in those spaces. You find that dynamic in I&I today.

In the 2010s, pharmas had little interest in obesity. You’d struggle to find pharma BD teams discussing their interest in acquiring assets in the space. Moreover, pharmas didn’t have an existing commercial force in obesity and lacked a clear playbook of how they might even go about commercializing such a drug. There are many stories of pharmas turning away promising obesity drugs, such as Roche in 2018 turning down the option to purchase Chugai’s Orforglipron, an oral GLP-1.

So how did pharmas end up developing obesity GLP-1s?

The above commentary that pharmas weren’t heavily investing in obesity appears somewhat contradictory to the fact that it was Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk that brought about the obesity revolution. The teams at both orgs that pushed forward the obesity angles were indeed prescient but it is important to note some of the serendipity element.

For most of history, GLP-1 was developed as a Type 2 Diabetes drug as opposed to an obesity one. After all, the origins of GLP-1 biology comes from examining insulin and glucagon pathways, and the first approved GLP-1 drug, Exenatide, was indicated for Type 2 Diabetes. And Type 2 Diabetes was an area whose work was led by pharmas much more than biotechs - any biotechs working on it would partner early on with pharma given the following:

T2D trials are notoriously large and lengthy, so it’s valuable for pharma to subsidize that cost

T2D drugs will likely need the help of pharma for commercial launch anyways, so partnership is inevitable

It’s no wonder that the first drug of biotech, Humalin, was partnered with Eli Lilly. The story of GLP-1 is not so dissimilar. The story of Hanmi Pharmaceuticals exemplifies this dynamic. This South-Korea based pharma was a major leader in GLP-1 development during the 2010s, alongside Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk, developing three different GLP-1 drugs: Efpeglenatide, a once-weekly GLP-1 agonist, Efinopegdutide, a once-weekly GLP-1/Glucagon dual agonist, and HM15211, a once-weekly GLP-1/GIP/Glucagon triple agonist. But the first two drugs were quickly licensed away to Sanofi and Janssen respectively in 2015 which ultimately never saw the light of day. What’s unfortunate here is that Hanmi actually had ambitions for obesity from its early days, contrarian to most other groups at the time, but its reliance on development partners made this difficult to realize.

When it inevitably became evident that GLP-1 drugs resulted in meaningful weight-loss in T2D patients, pharmas were the ones with access to these compounds and therefore ready to capture its value. And even this wasn’t so straightforward internally in these groups - the prescient scientists at Lilly and Novo faced headwinds in pushing forward this work but ultimately got the green light to see the generational outcomes we see today. For those interested in learning about the Novo story, I recommend the Acquired podcast episode that does a great job covering the story.

How can we better incentivize development of the next GLP-1?

Knowing what we know now about the GLP-1 revolution, investors and pharmas were mistaken in not investing more in weight-loss drugs in the 2010s which resulted in poor incentives for developing one. In my view, the fundamental inefficiency here was that it wasn’t clear a good obesity drug would be a $100bn+ outcome. If the industry could have peeked into the future and seen the monstrous sales of Mounjaro, I’m certain more investment would’ve gone in.

The challenge is that we really struggle with accurate drug forecasting, especially for emerging markets without an established product. The estimated sizes for such unestablished markets are often discounted too heavily, so the incentives for developing a drug is a fraction of the potential outcome size. Some markets that I think lend themselves to this dynamic are drugs for addiction, innovations in organ transplantation, drug + device combinations, psychedelic therapies, sarcopenia, frailty, or “drugs for aging” that appears to be a growing category.

Typically, such inefficiencies around market sizes are corrected by rewarding people who bet against it. In other words, companies and investors that take forward the contrarian opinion and prove to be correct are handsomely rewarded. The tech industry is littered with such examples. Take Uber for example - many believed Uber would have a capped upside given the limited market size of the taxi business, but ultimately the company proved to be correct and won big. But I suspect this approach doesn’t work as well in biopharma:

Getting permission to be contrarian in biopharma is difficult: if the goal is to prove a contrarian opinion around a drug market, the company needs to not only develop a drug with great clinical data, but also carry out a commercial launch. This requires convincing several groups of investors across multiple stages, which is already difficult to do in consensus markets let alone a non-consensus one.

Being contrarian and right still has limited upside for early-stage investors: in the above scenario, the major inflection point doesn’t come along until the commercial launch. In consensus areas, early-stage investors are rewarded as early as early clinical data because the market can anticipate that a good drug will have good sales, or increase likelihood of getting acquired. But you don’t get this in non-consensus markets. Not only does this meaningfully diminish IRR, but most early-stage biotech funds are structured as 10-year long funds which may not be long enough to see an early-stage project through to successful market adoption. So even if the company is ultimately successful, the original management team + investors may not see the reward. Alnylam today is a huge success but the Series A investors capture a fraction (if any) of that value.

To an extent, the pharma M&A model of biotech exacerbates this pathology as it incentives consensus behavior. Even if there are analysts that believe a market is be underappreciated, we’ll see diminished appetite for investments to the extent that the top 20 pharmas aren’t looking to acquire them. For what it’s worth, I believe this is the tradeoff of the pharma M&A model: it accelerates development of drugs in consensus markets by sweetening pie but discourages investments in non-consensus markets.

A potential solution would be the bolstering of an alternative commercialization path outside of pharma. This likely requires (1) commercialization costs to come down, (2) Contract Commercial Orgs (CCOs) to be much more effective, and (3) improved ability to forecast drug sales, but I believe this would allow the industry to take on a meaningfully different shape than today. In this scenario, pharma M&A dollars would be substituted with pools of “biotech growth capital” and project financing that already exists in a limited scope today led by groups like Blackstone and Royalty Pharma.

The ultimate remedy would be a crystal ball that allows us to input a target product profile and get back the outcome size for such a drug. This is the type of problem I can see modern-day AI making meaningful progress on and know a few promising groups making headway in. Good therapeutic hypotheses that allows us to actually tackle those markets will remain a bottleneck, but we can at least give them the incentives they deserve and create a more efficient market.

Very insightful thinking here. As someone who has worked a bit on the f/c side, I agree that the industry lacks the kind of imagination to appropriately size a non-existing market which makes it uninvestable for traditional VCs. There is also the need to build disease awareness (a horrible phrase admittedly) in clinicians and this normally percolates out over several years.

Could it just be luck? Consider:

-Most big pharma companies do very little basic R&D; Novo just happens to be one of the few

-GLP-1s were discovered for their diabetic therapeutic effects. The appetite suppression was chancy especially since the mechanism is different than the insulin effects

-Although this article isn’t wrong that the market size was uncertain, I don’t think it took a genius to say “if you had a drug that made people thin you’d be very rich”